In injection-molded part design, weld lines are one of the most underestimated weak points. When two melt fronts meet inside a mold cavity without enough temperature, pressure, or flow continuity, a thin unfused interface forms instead of true fusion.

On the surface it looks harmless. On the molecular level, it is a micro-crack where polymer chains never fully entangle.

When two melt fronts flow around obstacles and meet, the first contact happens near the cold mold wall. A frozen skin has already formed while only the core remains fluid. The fronts collide at nearly 180°, so their skins touch but cannot penetrate each other.

This creates a molecular boundary where chains are discontinuous and fibers are forced into weak orientations.

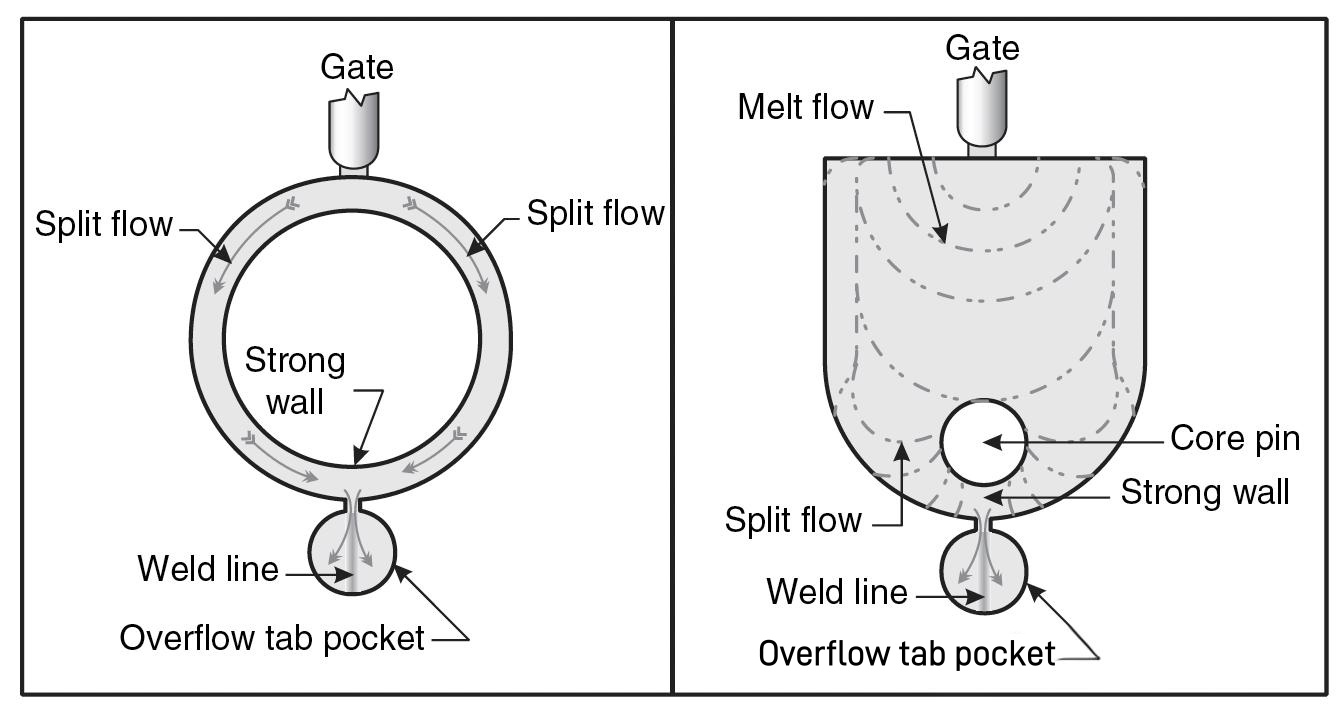

An overflow pocket prevents the flow from stopping at the weld line. Instead of freezing on impact, the melt keeps moving forward, giving the interface precious milliseconds for molecular healing.

Continuous flow maintains pressure and temperature, allowing chains to diffuse and entangle across the interface.

Shear heating raises the local temperature, softening the frozen skin and enabling true fusion.

The meeting angle gradually collapses from 180° to 0°, converting two opposing flows into one continuous stream and aligning fibers across the joint.

| Feature | Without Overflow Pocket | With Overflow Pocket |

|---|---|---|

| Interface Structure | Flat, sharp boundary | Gradual transition layer |

| Molecular Continuity | Broken chains | Fully interpenetrated |

| Fiber Orientation | Perpendicular collision | Interlaced & flow-aligned |

| Stress Distribution | Highly concentrated | Smooth and dispersed |

| Tensile Strength | −40% to −60% | 70–80% retained |

Instead of trying to hide or eliminate weld lines, smart mold design gives the melt somewhere to go. The overflow pocket acts as a pressure stabilizer, thermal buffer, and molecular repair zone.